If a job did not give him the chance to do enough good, to dig deep into understanding the human condition, he would not keep it, even if it offered money and stability. If a woman did not please his eye, stimulate his mind and share his passion for art, he could not fall in love. He would not even buy a pair of sunglasses if the label seemed tacky.

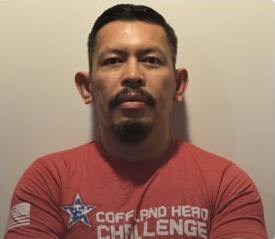

To understand why the 43-year-old Baltimore native ended up killed by a roadside bomb in Afghanistan last week, it is important to understand that quality above all. Because settling was never in his marrow, Coffland joined the Army as an intelligence specialist at an age when most men are working 9-to-5 and driving the kids to school.

Coffland’s biography suggests a man auditioning to become the next Indiana Jones: Playing professional football in Finland. Hunting crocodiles by night with the Pygmies of Gabon, Africa. Making men 20 years his junior look like slugs in Army boot camp. Coffland lived those and dozens of other adventures.

He did not bounce from job to job and country to country because he lacked purpose, loved ones said. In fact, he often moved to the next thing because no vocation made him feel he was doing enough for the greater good.

“He didn’t care about success in the conventional sense,” said his Gilman School classmate and longtime friend Dan Miller. “He had to find something that would be consistent with the purest expression of his spirit.”

Coffland watched as his friends married, had children and settled into prosperous careers. He knew they and his parents wanted the same for him.

“He respected his friends, adored them,” said his sister and closest friend, Lynn Coffland. “But he could not settle for what was not in his heart.”

“Chris had a bear inside of him that growled from time to time and compelled him to the next place,” said Mike McGrann, who became Coffland’s friend when they were the only two Americans playing football on the Helsinki Falcons.

Coffland, who will remembered at a funeral Mass at 11 a.m. Saturday at the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen, lived a life full of complexities and seeming contradictions.

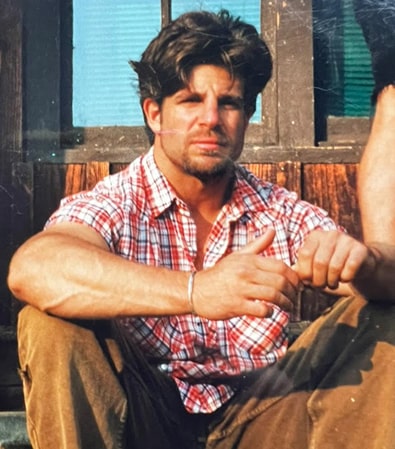

He cared little for money and often said he needed nothing more than the contents of a backpack. But he cared deeply about aesthetics and accumulated a sprawling collection of art, vintage jewelry and furniture.

He was a steadfast friend, known for showing up spontaneously to help with housework or to provide comfort in a time of emotional need. But he could never commit to the same job or hometown for more than a few years.

He adored women and forged instant connections with his friends’ children. But he could never find a romance that satisfied him for long.

He was a warrior on the athletic field, a naturally small man who loved to hurl his body at bigger targets. But off it, he showed empathy for people from all walks of life, engaging relative strangers in deep conversations about God and the purpose of life.

He was the freest of spirits. But he gave his life to one of his country’s most regimented institutions.

No matter where he went, Coffland made friendships of unusual depth, often in a matter of days. Whether bartending at Vin in Towson or meeting non-English speakers on a trip to Russia, he had no reservations about putting his most essential thoughts on the table or about asking penetrating questions of others.

“Chris was just one of those people who was worth getting to know, someone you could always engage in an interesting conversation,” said John Patton, his anthropology adviser at Washington State University. “He had this knack for being sympathetic, for knowing what you needed before you did and stepping in.”

He loved to help a friend in need and often did so across great distances and without being asked.

He once chopped all of Patton’s firewood for him without ever discussing it. When the professor’s 10-year-old son felt lonely after the family moved from Colorado, Coffland took him to football games and became his de-facto big brother.

When Miller’s mother, Anna, moved from her house in Roland Park, Coffland showed up out of the blue to haul boxes. The next time she moved, he did it again, unannounced.

Coffland grew up in Fullerton Heights and Timonium, the youngest of five children. His father, David, was a burly former football player and longtime traveling salesman. His mother, Antoinette, showed her love with sumptuous Italian meals. From an early age, Coffland shared an uncommon bond with his sister Lynn, eight years his senior.

Her teenage dates had to accept that an outing with her was also an outing with Chris. The two of them loved to scour the thrift shops along Maryland Avenue for cheap paintings and sculptures. He loved to buy bold silver rings, fat leather bracelets and flashy cuff links adorned with dice, poodles and other offbeat images.

“Could you imagine wearing this?” his sister asked, hefting a bronze necklace that must have covered half his chest. “Somehow, he did it and he still looked hot!”

They developed their own language. Her white Honda was “the egg.” A painting with three-dimensional yellow shapes was “potato chip.” After he lived in Australia for a year, they called each other “mate.” When he came back to Baltimore from his latest adventure, he usually stayed at her house in Homeland.

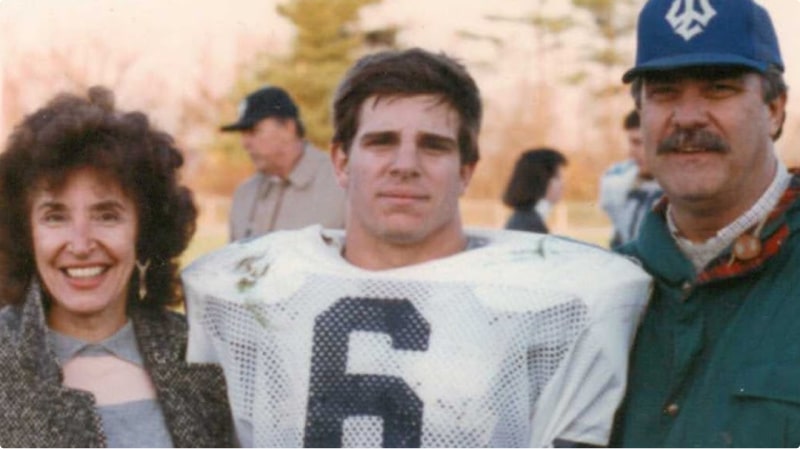

Though Coffland came from a blue-collar household, his athletic and artistic talents earned him a scholarship at Gilman. At summer football practice before ninth grade, he weighed maybe 115 pounds but happily went toe-to-toe with 200-pound senior starters. That impressed the classmates who would become his close friends for life.

He never got past 160 pounds in high school and wasn’t particularly fast, but he played safety and teammates knew that if a pile began to form around the opposing ball carrier, No. 23 would come recklessly flying into the picture.

“For football, the best kind of person is one who plays with absolute abandon but does it within the structure of a team concept,” said Sherm Bristow, his coach at Gilman. “That was Chris.”

Off the field, he lived by his own code, one that led him to confront boys who made fun of those who were less privileged but that also led him to odd choices, like wearing a pajama shirt with his blazer and tie.

“People liked him and admired him, but they might have been a little afraid of him,” Miller said. “He had this code of ethics, and if you offended his sense of propriety, he was going to get in your grill.”

Coffland wrote about those years in a letter to the Army, explaining his qualifications for intelligence work.

“Until freshman year in high school, I never knew what a country club was,” he said. “Now, I was attending debutante parties for the most well-heeled of Baltimore society. I mention this because the dichotomy offered in social circles of my younger years had a unique and profound impact on my ability to effortlessly interact with anyone from any walk of life. I feel as comfortable talking to a head of state as I do a second-shift factory worker, and since I know both worlds, I am able to integrate into either without a trace of unfamiliarity.”

In college, at Washington & Lee, Coffland became captain of the football and lacrosse teams. His lacrosse teammate and longtime friend, Carlos Milan, said he had “the highest moral fiber of anyone I ever knew.”

“Whether on the team or with a friend, it was in him that if duty called, he was drawn to it,” Milan said.

After graduation, he wanted to travel and he wanted to play football as long as he could. That quest took Coffland to Finland, where he and McGrann, a 6-foot-6 linebacker from Cornell, were the American ringers in a nascent European league. “He was enigmatic, this tough, hard-nosed college athlete who wanted to have these incredible debates about theology and the role of God in our lives,” McGrann remembered.

He gave Coffland a copy of the spiritual book “The Road Less Traveled.” Coffland read it from back to front.

After his playing days in Finland, he coached for an Australian league based in Melbourne and ran the Hanaua Hawks football team in Frankfurt, Germany. He later wrote proudly that he turned every team he coached from a loser to a winner. “Using the same limited athletes as the previous year, I never coached a team that lost more than three games in a season,” he said. “This fact has nothing to do with expertise in strategy or simple blind luck, instead it has everything to do with my ability to alter the mindset of individuals to do things they previously never thought possible.”

Coffland’s fascination with people and their motivations led him to his next great source of adventure, the study of anthropology. He pursued a doctorate at Washington State and settled on the evolution of culture as his specialty. For field work, he traveled to remote areas of the rain forest in Gabon and lived with a tribe of Pygmy hunters called the Bakola. He slept in a grass hut, survived on one meal a day (usually a forest animal that he had helped kill) and learned to evade elephants and leopards.

“In every situation, the one tool in my arsenal was my ability to interact with others,” he wrote later.

The one threat he could not avoid was a falling tree that left him bleeding from the ears and badly banged up. He had to come home without sufficient research, and instead of writing another dissertation on a topic that failed to inspire him, he discontinued his studies.

He always wished to finish his degree, however, and spoke to Patton about studying the evolution of suicide bombers in Afghanistan as a possible dissertation topic.

Back in the U.S., friends often joked about his ability to live sans possessions. During one stretch in Baltimore, he stayed in a small space over Club Charles, refrigerating his food by keeping it on the windowsill and telling time by the passing of city buses. The few possessions that mattered — his art, his vintage motorcycle, his restored 1968 Camaro with no air conditioning — stayed with friends or family.

He worked as a director of student housing at the Art Institute of Seattle and at Loyola Marymount Institute in Los Angeles. In 2005, he came back to Baltimore, helping local artist Eric Anderson to design and market custom furniture and bartending at night. He became a favorite “uncle” to his friends’ kids and with his taut physique, electric smile and fearless patter, had a succession of girlfriends.

None of it was enough.

The idea of a 41-year-old deciding that he had to beat the age deadline and sign up for wartime military service might seem unfathomable to most. But Coffland’s family and friends were not shocked. They knew he felt called to serve his country and that he had contemplated enlisting throughout his adult life. Only his reservations about the Army’s rigidity and long training commitment kept him from signing up sooner.

“What surprised me was that he had never conformed, but he was choosing a life that was all about conforming,” Lynn Coffland said. “What he said was that he lived his life as a free spirit but conformed when necessary. And this was necessary to him.”

Coffland considered a six-figure offer to work as a corporate recruiter for a former classmate. But after analyzing the situation from every angle and talking to recruiters and intelligence specialists, he signed on with the Army Reserves in December 2007, a month before he turned 42. He headed to Fort Sill in Oklahoma for boot camp.

Though Coffland was older than the parents of some fellow soldiers, “he was probably in better shape than anybody there,” said Tom Feehan, his roommate.

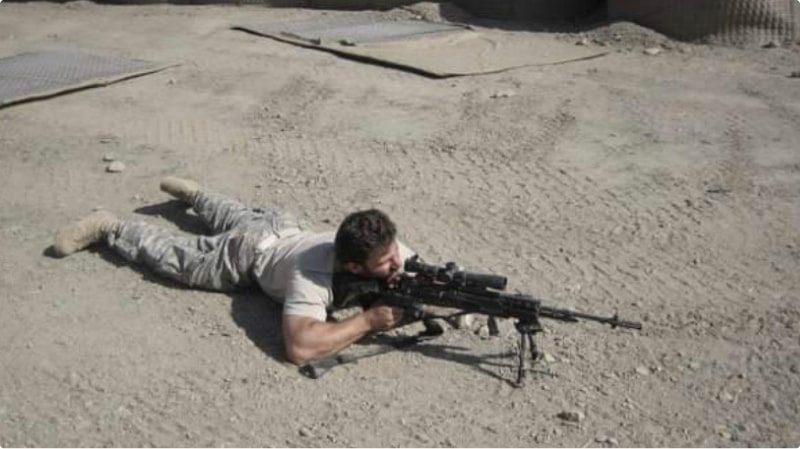

The same curiosity that had caused him to start serious discussions with his friends’ parents and plunge into the African jungle for research made Coffland turn to intelligence as a specialty. He believed he would be the perfect guy to swoop into a village after a bombing and get the natives talking about what had happened. He figured he might later work for a national intelligence agency.

“The work was perfect for him, absolutely perfect,” Feehan said. “Basically, our job is to go out and talk to people and find out what’s going on. That came to him very naturally.”

A performance evaluation from intelligence school praised Coffland for “communicating his ideas, building rapport, and controlling the outcome of all his personal meetings in a variety of challenging situations.”

By last summer, he knew he was headed for Afghanistan.

As bold and fearless as he could be, Coffland approached his deployment with a full awareness that he could be killed. In his last conversations with friends, he sounded sober about the prospect but eager to be dispatched to a dangerous area where his skills would be tested.

In an e-mail to his sister the night before he was killed, Coffland joked that he was getting to use “an extraordinary amount of James Bond gadgets” and complained about the itchiness of his beard, grown full to help him fit in with the locals. But in another e-mail, copied to her by accident, he spoke of numerous roadside explosives in the area and said “it’s only a matter of time.”

The cause of Coffland’s death, 2 1/2 weeks after he arrived in Afghanistan, is likely to be investigated for months. But his commander called and told his sister he had been on the way to investigate another roadside explosion in the remote Sayed Abad district when his vehicle was hit Nov. 13.

A group of 20 relatives and friends traveled to Dover, Del., the next night to watch his coffin come off a military plane. To his sister, the scene seemed terribly wrong. Chris Coffland had spent his whole life refusing to conform, a round peg that others could never hammer into a square hole. Yet there he lay, in a box. She wanted to crawl in and free him.

-By Childs Walker Baltimore Sun – 2009